- The CEO Presidency

For years, a large segment of the American electorate embraced the idea that government should be run more like a business. The pitch was simple and emotionally compelling: Washington was bloated, slow, and tangled in bureaucracy, and what the country needed was a hard charging executive who would operate like a chief executive officer. That framing was not accidental. Donald Trump built his public persona on being a decisive corporate leader, a brand conscious dealmaker, and a boss who rewards loyalty and punishes disloyalty. In his own business writing, particularly in The Art of the Deal, he emphasizes control of narrative, aggressive reputation management, and tight personal oversight of high stakes matters. When voters chose that model, they also, whether intentionally or not, imported the rules of corporate accountability into the White House.

Understanding corporate structure is essential to understanding how responsibility flows. In large companies, the CEO is not a distant symbolic figure. The chief executive sets culture, chooses senior leadership, defines priorities, and shapes how the organization responds to threats. Sensitive legal issues, public relations crises, and matters that could affect the company’s long term brand value are not left to chance. They are elevated. General counsel, communications executives, and trusted senior advisors brief the CEO, outline risk, and align on strategy. Even when a CEO does not personally draft every memo, the direction is clear: protect the organization, contain damage, and control what becomes public. That is not conspiracy thinking. It is standard corporate governance.

Trump’s management style, both in business and in office, closely tracks that model. He consistently favored personal loyalty as a primary qualification for influence. Advisors who defended him publicly were elevated. Those who contradicted him were marginalized or removed. Decision making was centralized, messaging tightly controlled, and internal disagreement often framed as betrayal. That structure mirrors companies built around a dominant founder or brand personality, where authority concentrates at the top and major reputational decisions reflect the will of the chief executive. Under that system, it is implausible that a politically explosive, legally sensitive, and globally scrutinized document process would unfold without executive level awareness of its contours and consequences.

The handling of records tied to Jeffrey Epstein falls squarely into that category of high risk, high visibility corporate crisis. Epstein’s crimes involved the sexual exploitation of minors and young women, trafficking across jurisdictions, and an international web of wealthy and powerful contacts. The public interest in transparency is not abstract. For survivors, these records represent validation, accountability, and the possibility that those who enabled or benefited from abuse might finally face scrutiny. When large volumes of material connected to that case are reviewed, filtered, and redacted, it is not a routine clerical exercise. It is a strategic decision about exposure, liability, and reputational fallout for individuals and institutions.

In a corporate environment, a review and redaction process of that magnitude would be classified as a top tier risk event. Legal departments would assess defamation exposure and criminal liability. Communications teams would model media response. Senior leadership would weigh political and financial consequences. Most importantly, the CEO would be briefed on the stakes and the recommended path forward. Even if the CEO did not personally edit documents, the boundaries, priorities, and end state would be set at the executive level. That is the chain of command logic that corporate advocates often praise as decisive and efficient.

When this same logic is applied to the presidency, the conclusion is uncomfortable but consistent. Presidents appoint agency heads, influence Department of Justice priorities, and are kept informed on matters with significant political and legal impact. The idea that an issue involving global attention, powerful associates, and potential institutional embarrassment would move through the system with no executive level understanding runs counter to how both corporate and political power typically operate. In the CEO model, leaders do not get to claim ignorance of outcomes that directly affect the organization’s reputation and legal exposure. Responsibility flows upward, not downward.

This is not just a matter of abstract governance theory. It intersects with real human suffering. The victims tied to Epstein’s operation were not political talking points. They were young people coerced, manipulated, and abused by someone shielded for years by wealth and influence. For many survivors, every withheld name and every blacked out section feels like another instance of the powerful being protected while the harmed are asked to accept partial truth. The moral weight of that reality is heavy. When a system prioritizes reputational management over full transparency, it risks deepening the trauma of those already failed by institutions.

There are also individuals who have been identified in various legal and investigative contexts as part of Epstein’s broader network of enablers or associates. Allegations, civil findings, and reporting have named figures such as Leslie Wexner, Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, Salvatore Nuara, Zurab Mikeladze, Leonid Leonov, and Nicola Caputo in connection with aspects of Epstein’s operations or logistics, though the legal status and degree of responsibility vary by case and jurisdiction. The larger issue is not the guilt of any single person, but the pattern of influence, access, and insulation that surrounded Epstein for years. When records connected to that ecosystem are filtered from public view, questions of accountability naturally extend to the highest levels of decision making.

Many Americans supported a CEO style presidency precisely because they believed it would cut through bureaucracy and hold institutions accountable. They wanted clear lines of authority and decisive leadership. But corporate structure has a built in trade off. The same concentration of power that allows fast, forceful action also concentrates blame when outcomes appear to protect the organization over the vulnerable. In business culture, a chief executive is praised for strong control in good times and held responsible for major damage control decisions in bad times. The position does not allow selective ownership of only the positive results.

If the presidency is treated as a corner office and the nation as an enterprise, then the logic of corporate accountability follows. A large scale, reputation sensitive information management process tied to one of the most notorious sex trafficking cases in modern history is not a minor bureaucratic footnote. It is the kind of event that, under a CEO model, would be known, shaped, and ultimately owned by the person at the top. Whether through direct instruction or through the culture and expectations set by leadership, the responsibility attaches to the executive. That is the standard corporate America applies to its own leaders, and it is the same standard many voters asked to be applied to government.

- The Epstein Files: Delayed Truth and Bi-Partisan Protection of the Powerful

Early Promises, Quiet Warnings, and Political Crossovers

Donald Trump recaptured the presidency in January 2025. Boom! This instantly rekindled hopes among his supporters. They thought the secrets of Jeffrey Epstein’s exploits, and his powerful friends, would finally come to light. On the 2024 campaign trail, Trump had signaled he would open up all the government’s Epstein files. Soon after taking office, his newly appointed attorney general, Pam Bondi, threw fuel on the fire! She suggested on live TV that an Epstein “client list” was literally sitting on her desk. That was a dramatic tease! Many expected imminent revelations, an explosion of truth! In reality, what followed was a pattern of hesitation and obfuscation. A pattern that cut right across partisan lines.

Behind closed doors, a quiet warning came in May 2025. Bondi privately told President Trump that his own name appeared “multiple times” in the Epstein case files under review by the Justice Department and FBI. Serious stuff. She and Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche immediately recommended against any broad public release of those documents. They cited the inclusion of child sexual abuse material and sensitive personal information of victims. Trump acquiesced. He told Bondi he would defer to the Justice Department’s judgment not to release additional Epstein files. (Later, when reporters pressed him about Bondi’s warning? Trump denied being told his name was in the files! He dismissed the entire issue as “fake news” concocted by his foes. Big denial.)

It’s worth noting: when Epstein’s abuses occurred, Trump was often a Democrat. He traveled in the same elite circles as Epstein’s other friends. In fact, Trump switched his party affiliation to Democrat in 2001 and remained a registered Democrat for the next eight years. He even mused in 2004 that he “identified more as a Democrat” at the time. This historical footnote is crucial. It underscores how Epstein’s web of influence spanned political lines – Trump, Clinton, and others partied in the same New York and Palm Beach social scene. The Epstein scandal was never going to be a neatly partisan affair, no matter how much each side prefers to blame the other.

The “Special Redaction Project” and Systemic Coverup

Even as Bondi was publicly hinting at bombshell evidence, the FBI was racing behind the scenes. They were sanitizing Epstein’s files! Internal correspondence later revealed that FBI Director Kash Patel (installed by Trump) launched an all-hands effort in early 2025. The goal? To review and heavily redact Epstein-related records in case of a forced disclosure. The bureau’s Winchester, VA records facility became ground zero. Agents dubbed it the “Epstein Transparency Project” or the “Special Redaction Project.”

Patel ordered roughly 1,000 FBI personnel to undergo a crash course in redaction techniques. Between January and July, the Bureau racked up nearly $1 million in overtime costs on Epstein file review. There was a frantic redaction sprint in March 2025 alone, accounting for over 70% of those overtime hours. Unbelievable dedication to censorship! Emails obtained via FOIA show newly appointed FBI deputy director (and Trump ally) Dan Bongino was looped into these efforts on literally his second day in office.

The implementation of the Epstein Files Transparency Act has resulted in what can only be characterized as a flagrant and systemic coverup within the American legal apparatus. The statutory deadline for the full release of these records was December 19, 2025. The resulting disclosure, however, represented only a minuscule fraction of the required material. It fell far short of the transparency mandated by law.

Publicly, officials justified the painstaking vetting by citing the need to remove child pornography and protect the privacy of victims. In May, Bongino assured the public that “voluminous amounts of downloaded child sexual abuse material” and victim statements had to be handled correctly, even as he acknowledged the public’s desire for transparency. But skeptics wondered: was something, or someone, else being protected? Indeed, once Bondi informed Trump that his own name surfaced in the trove, the administration’s enthusiasm for “full transparency” seemed to evaporate overnight.

On July 7, 2025, Bondi abruptly announced that the Justice Department’s exhaustive review had uncovered no incriminating “client list” after all. She declared the Epstein case effectively closed and said no further files would be released. This reversal shocked many of Trump’s populist supporters, who felt betrayed after months of promises. Red flags immediately went up: only weeks earlier Bondi had boasted of explosive secrets, and the FBI had been urgently redacting documents by the truckload. Now the official line was that nothing of prosecutorial value was found! To critics, it looked like a classic Washington cover-up. One seemingly engineered to protect high-profile figures from both parties.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) has engaged in indefensible redaction practices. They completely blacked out hundreds of pages, specifically documents 6109, 6209, and 6309, without providing the legally required justifications to Congress. This level of obfuscation extended to a 119-page grand jury indictment! That indictment remained entirely redacted despite a federal court order explicitly demanding that these records be made public. Such actions suggest a clear “playbook” where the administration takes previously available information, applies heavy redactions, and then presents it as a new, transparent disclosure.

The administration’s approach has been further marked by a calculated effort to scrub specific political figures from the record. Reports indicate that thousands of agent hours and nearly a million dollars in overtime were dedicated specifically to redacting Donald Trump’s presence in the files. A notable instance of this manipulation involved file 468, a previously unseen photograph of Trump. It was briefly published, then deleted from the public database, and only restored after intense public scrutiny and massive backlash.

Congress Intervenes: A Transparency Law and a Shutdown Showdown

Bondi’s July announcement and the administration’s stonewalling galvanized an unusual left-right coalition in Congress to force the issue. Within days, bipartisan legislation was introduced in the House to compel the release of all Epstein files. The Epstein Files Transparency Act was sponsored by liberal Democrat Ro Khanna and conservative Republican Thomas Massie. An unlikely pairing! It reflected a shared frustration with the Justice Department’s secrecy.

Yet GOP leadership, closely aligned with Trump, resisted the bill at every turn. House Speaker Mike Johnson, one of Trump’s staunch allies, used his powers to stall the proposal for months, even keeping the House of Representatives in recess for weeks to delay a potential vote.

That fall, a new obstacle emerged: a federal government shutdown in October 2025 over unrelated budget disputes. Johnson seized on the shutdown as a pretext to prolong the House recess. He thereby froze a procedural maneuver (a discharge petition) that reform-minded lawmakers were using to force a vote on the Epstein files bill. This was raw procedural hardball! The Speaker even refused to swear in a newly elected House member (a Democrat whose signature was needed to hit the 218-signature threshold) until the government reopened. In short, the transparency legislation was literally being held hostage to the federal funding impasse, underscoring how far the President’s allies would go to keep the Epstein files buried.

Johnson publicly argued there was no need for a law since a House committee was supposedly investigating Epstein anyway. (The House Oversight Committee had indeed obtained “tens of thousands of pages” of Epstein-related emails and evidence, including a “salacious drawing” Trump had once sent Epstein for his birthday. Those materials hinted at embarrassing connections, but did not satisfy demands for full disclosure.) Privately, however, even some Republicans grew uneasy with the optics of blocking the Epstein files. Four GOP representatives broke ranks and joined every Democrat in signing the discharge petition. The dam was about to break.

Ultimately, the dam did break. After 21 days, the October shutdown ended and the House reconvened. On November 12, 2025, Khanna and Massie’s discharge petition finally secured the 218th signature, over Speaker Johnson’s objections. Facing overwhelming bipartisan pressure, House leaders relented and scheduled a vote. The result was a lopsided 427–1 House vote to release the files (the lone dissenter was a Republican). The Senate followed suit by unanimous consent. Even President Trump, sensing the political winds, reversed his stance! He quickly signed the Epstein Files Transparency Act into law on November 19, 2025. What his administration had spent months resisting had become inevitable. The new law gave Attorney General Bondi 30 days (until December 19, 2025) to make “all unclassified records, documents, communications, and investigative materials” on Epstein and his associates public in a searchable database, with only narrow exceptions for protecting victims and truly classified intel.

Deadline Day: A Partial Dump and Missing Pieces

December 19, 2025, was supposed to be the day of full truth! Instead, the Justice Department released a cache of Epstein files on the deadline, but it immediately drew fire. It was incomplete and heavily redacted. Thousands of pages of documents, photos, and records were posted to a DOJ website, but journalists and lawmakers noted that vast swathes of text were blacked out and, curiously, very few documents mentioned Donald Trump at all, despite his well-known friendship with Epstein.

By the DOJ’s own admission, the initial dump was only a partial release. Bondi’s team said more would trickle out in coming weeks, well past the law’s 30-day deadline. In other words, the DOJ failed to comply with the letter of the law. They missed the date and withheld an unknown number of records. This decision, made unilaterally by the very officials who had fought disclosure, sparked bipartisan outrage.

Democratic House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries blasted the DOJ’s foot-dragging! He called for a “full and complete investigation” into why the release “fallen short of what the law clearly required.” Representative Khanna, co-author of the law, went so far as to suggest Attorney General Bondi should be impeached for defying Congress’s mandate. Even some Republicans echoed frustration that the spirit of transparency was being flouted. The law had required DOJ to either release everything or provide detailed justifications for any withheld items within 15 days; instead, weeks of silence and selective disclosures followed, completely eroding trust.

Furthermore, the release appears to be heavily curated. A calculated move to highlight political enemies while protecting others. For example, the DOJ included a long-public fundraiser photograph featuring Bill Clinton and Michael Jackson, but redacted the children in the image as if they were Epstein’s victims! This inclusion of non-relevant, public information under the guise of sensitive material points to a combination of incompetence and deliberate deception.

The controversy deepened the weekend after the release. Tech-savvy observers noticed something alarming: at least 16 images and documents vanished from the DOJ’s public Epstein files website shortly after they were posted. Among them was that photograph of Epstein’s desk in his Manhattan townhouse (evidence photo #468) in which two pictures of Donald Trump are visible. The unexplained removal of that image set off a firestorm. Congressional Democrats on the Oversight Committee publicly accused the administration of scrubbing the files to protect Trump, calling it “a White House cover-up.”

By the next day, the Justice Department restored the Trump-related photo to the online database. Their explanation was unusual: DOJ said it had temporarily pulled the image “out of an abundance of caution” after prosecutors flagged that it might contain identifiable victims, but after review they “determined there is no evidence that any Epstein victims are depicted” and thus reposted it unaltered. Deputy AG Todd Blanche insisted the removal “had nothing to do with President Trump” and that DOJ was simply responding to concerns from victims’ advocates about possibly under-redacted photos.

To be fair, victims’ rights groups did raise serious complaints about the initial release, but for the opposite reason one might expect. Prominent attorney Gloria Allred, who represents several Epstein survivors, admonished DOJ for under-redacting certain files: she pointed out that some victims’ full names and even photographs were erroneously left exposed in the document dump. One Epstein accuser wrote to DOJ that it was galling her name was published without warning when for years she had been denied access to her own file. The optics were terrible all around. DOJ was being lambasted for over-redacting names of VIPs, and being chastised for under-redacting sensitive victim info.

Blanche defended the slow, rolling disclosure. He argued that the statute also obligates DOJ to protect victims, implying that meeting the deadline would have meant reckless unmasking of private details. But the law’s supporters retorted that DOJ had had plenty of time (almost a year since Trump’s election, and decades since the crimes) to prepare the files properly. To them, the eleventh-hour concern for victims looked conveniently like a smokescreen to shield political allies.

Institutional failures are also evident in the handling of related evidence and personnel. The Bureau of Prisons (BOP) footage, for instance, is riddled with inconsistencies, jump cuts, and unexplained sightings of individuals. Additionally, Ghislaine Maxwell reportedly received a special waiver from the DOJ to serve her sentence in a comfortable facility for which she does not qualify, despite being a convicted sex criminal. These ongoing violations of the law and the continued “drip-feeding” of redacted information ensure that the truth regarding the Epstein case remains largely obscured.

Allegations have even surfaced that political tampering skewed the redactions. A hot-mic rumor made the rounds in September 2025 that an acting DOJ official quipped about blacking out “all Republican names” while leaving Democrats’ names visible in the Epstein documents. Jeffrey Epstein’s own brother claimed in a televised interview that he was told Trump officials were “scrubbing the files to take Republican names out,” essentially sabotaging the release.

These claims remain unproven, but they highlight a climate of profound mistrust. Members of Congress have formally asked the FBI to explain the chain-of-custody and integrity of the Epstein evidence, demanding assurances that nothing has been altered or destroyed during the months of secret review. In one pointed letter, a congressman noted the “rich and powerful have not been held accountable” and warned against “selectively releasing and withholding files” to protect officials of any party. The Justice Department, for its part, has not commented on these tampering allegations. They stick to the line that any delays or redactions were done solely to comply with the law and protect the innocent. But after so many twists, few observers are taking DOJ’s word at face value.

Who’s Who in the Files: Democrats, Republicans, and Royalty

One reason the Epstein case has transfixed the public: so many prominent names are implicated across the political spectrum! The files and prior court evidence make clear that Epstein cultivated relationships with elites of all stripes:

Democrats

- Former President Bill Clinton stands out among Epstein’s associates. Clinton famously flew on Epstein’s private jet (the “Lolita Express”) numerous times, and his name appears throughout Epstein’s schedules and contacts.

- The December document release even included photographs of Clinton apparently relaxing in Epstein’s company – one newly public image shows Bill Clinton in a hot tub with Epstein’s confidante Ghislaine Maxwell and a young woman, circa the early 2000s.

- Other Democrats surfaced as well: former New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson and ex-Senator George Mitchell, for instance, were named in prior legal filings by Epstein accusers (allegations they have denied).

- The Epstein files also contain correspondence involving Larry Summers, a Treasury Secretary under Bill Clinton, and Reid Hoffman, the billionaire LinkedIn co-founder and major Democratic donor. These documents don’t implicate them in crimes, but they underscore Epstein’s broad network among influential Democrats.

Republicans

- The most notable Republican in Epstein’s orbit is Donald Trump himself, Epstein’s friend and social neighbor in Palm Beach for many years (before a falling-out around 2004).

- Trump’s name appears multiple times in the Epstein case files reviewed by the FBI and DOJ, although officials have stressed that mere appearances of a name are not evidence of wrongdoing.

- In fact, one newly revealed 2019 email from Epstein to a reporter cryptically stated that “Trump knew about the girls,” though Epstein did not elaborate on what he meant. Given Trump’s high office, any hint of his awareness or involvement has been explosive.

- Another Republican-adjacent figure in the files is Steve Bannon, Trump’s onetime strategist – emails released by a House committee show Epstein corresponding with Bannon in 2019, suggesting even Trump’s inner circle stayed in contact with Epstein.

- It’s also worth recalling that key players in Epstein’s 2008 sweetheart plea deal included Republicans: Alex Acosta, the U.S. Attorney who approved Epstein’s non-prosecution agreement (and who later became Trump’s Labor Secretary), and Ken Starr, the former GOP special prosecutor who quietly served on Epstein’s defense team. Epstein had a knack for ensnaring GOP and Democratic luminaries alike.

Global Elite

- Epstein’s reach extended beyond American partisans. British royalty, for example, became embroiled in the saga via Prince Andrew (formally Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor).

- Andrew was a frequent Epstein companion and was accused by Virginia Giuffre of sexual abuse (he settled her civil claim without admitting fault). The files include Andrew’s name in emails and visitor logs, and his disgrace has been so total that the King stripped him of his titles.

- High-profile international figures such as former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and billionaire business leaders also pop up in Epstein’s records, reflecting how his black-book of contacts spanned continents.

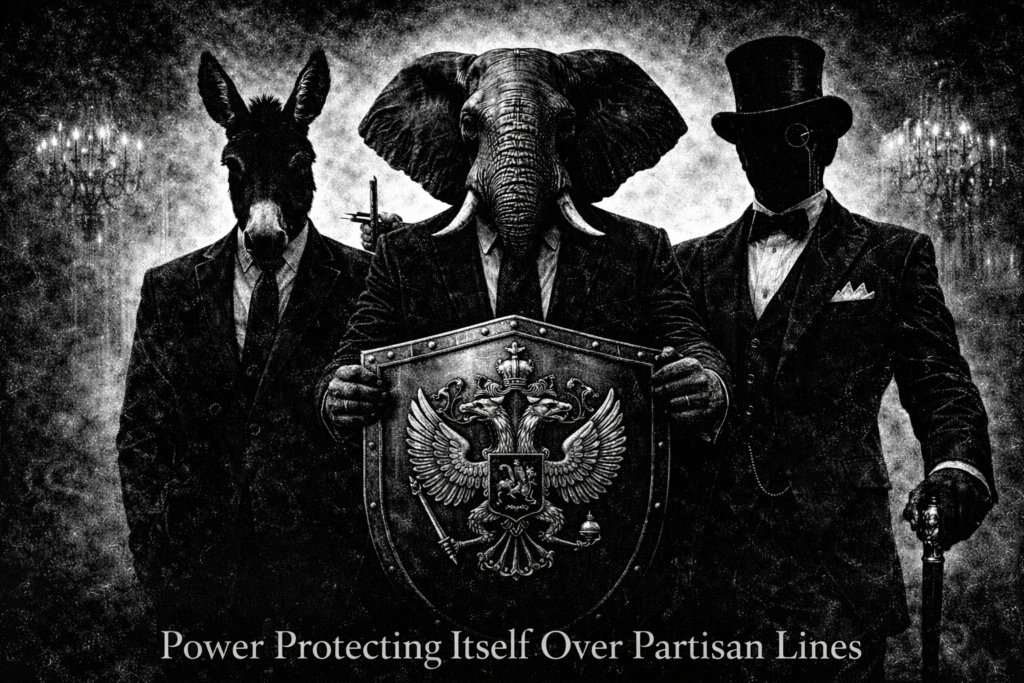

Crucially, Trump’s past life as a Democrat underscores the incestuous nature of this elite world. During the height of Epstein’s activities in the early 2000s, Trump and Clinton were not in opposing camps at all – they were fellow members of the Manhattan and Mar-a-Lago jet set. Partisan affiliation was fluid (Trump himself was a Democrat from 2001 to 2009), and Epstein’s rolodex was ecumenical in its inclusion of power players. This context makes it harder for either major party to claim the moral high ground. The Epstein scandal is less about left vs. right than it is about top vs. bottom: the elite protecting their own.

The tortuous saga of the Epstein files, from Trump’s campaign promises to Bondi’s backtracking, from the FBI’s secret “Special Redaction Project” to Congress’s forced hand, and finally to the begrudging, partial release and its aftermath, reveals a sobering truth. America’s political establishment, both Republican and Democrat, has repeatedly prioritized the protection of powerful figures over full accountability. Each twist in this story has featured lofty rhetoric clashing with self-interested reality. Republicans stalled and sabotaged a transparency law ostensibly to guard a Republican president, even as many of Epstein’s most scandalous connections were with Democrats. Democrats now decry a “cover-up,” but some were notably quiet when Epstein’s crimes first came to light years ago, perhaps because their own leaders were implicated. In the end, the impulse to shield the elite transcended party affiliation.

This entire saga suggests a massive bamboozling of the American public. Trump has consistently shown to be the opposite of what many who supported him thought he was. It’s an infuriating deception, reminiscent of how America was bamboozled by Big Pharma before, but this time by the very president that helped get that Big Pharma powerplay into action in the first place.

To be clear, the Epstein files did finally begin to see sunlight thanks to rare bipartisan unity and public pressure. Yet the initial document dump, dumped on the last possible day, rife with redactions, and apparently curated to spotlight certain individuals while obscuring others, has satisfied almost no one. It has instead reinforced cynicism that the system is still covering for its friends. Behind closed doors, the real secret is this: neither the left nor the right actually cares about full exposure. They don’t want to expose the beloved leaders of their failed two-party system. If they truly cared, they would be shouting this from the rooftops! Instead, it’s just the few who have followed this case through its entirety, not just the bandwagon jumpers, who remain dedicated to the truth.

As one observer quipped, “If you’re a billionaire with friends in high places, justice bends to accommodate.” The fact that Ghislaine Maxwell (now a convicted sex trafficker) was interviewed by Trump’s DOJ only to exonerate Trump of any misconduct, and immediately afterward received a transfer to a more comfortable prison, is a stark example of how favors get traded at the top. It’s the kind of quid pro quo that breeds public distrust.

Rather than a cathartic exposure of Epstein’s darkest secrets, the 2025 release saga became a mirror held up to America’s ruling class. We saw partisanship weaponized not to illuminate the truth, but to obscure it. We saw #ReleaseTheFiles T-shirts on the far right, and outraged speeches on the left, but behind closed doors the instinct… it remains.

Sources

- ABC News.

“Pam Bondi Told Trump His Name Appeared Multiple Times in Epstein Files, Sources Say.”

ABC News, May 2025. - Reuters.

“Trump Says He Will Defer to Justice Department on Release of Epstein Files.”

Reuters, May 2025. - Associated Press.

“Trump Campaign Promised Epstein Transparency, Administration Later Backed Off.”

Associated Press, January 2025. - Federal Election Commission.

“Voter Registration and Party Affiliation Records of Donald J. Trump.”

Public records, New York and Florida, 2001–2009. - New York Times.

“Trump’s Shifting Political Identity Over the Years.”

New York Times, archival reporting. - Reuters.

“FBI Conducted Extensive Review of Epstein Records Ahead of Possible Disclosure.”

Reuters, June 2025. - The Daily Beast.

“Inside the FBI’s ‘Special Redaction Project’ for the Epstein Files.”

Daily Beast, July 2025. - House Committee on Oversight and Accountability.

“Transcribed Interview and Document Production: Epstein-Related Evidence.”

U.S. House of Representatives, 2025. - The Guardian.

“US Lawmakers Force Vote to Release Epstein Files After Months of Delay.”

The Guardian, November 2025. - Congressional Record.

“Epstein Files Transparency Act: Floor Debate and Final Vote.”

U.S. Congress, November 2025. - Associated Press.

“Trump Signs Epstein Files Transparency Act After Bipartisan Pressure.”

Associated Press, November 19, 2025. - Reuters.

“Justice Department Misses Deadline, Releases Partial Epstein Document Cache.”

Reuters, December 19, 2025. - PBS NewsHour.

“At Least 16 Epstein Files Temporarily Disappear From DOJ Website.”

PBS NewsHour, December 2025. - Fox News.

“DOJ Epstein Disclosure Draws Fire After Website Glitches, Missing Files.”

Fox News, December 2025. - Department of Justice.

“Statement Regarding Temporary Removal of Epstein-Related Images.”

DOJ Press Release, December 2025. - House Oversight Committee (Democratic Staff).

“Letter to DOJ Regarding Removal of Trump-Related Epstein Materials.”

December 2025. - Gloria Allred, Esq.

Public statements and filings on behalf of Epstein survivors regarding under-redaction.

December 2025. - U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York.

Giuffre v. Maxwell, unsealed filings and exhibits.

2019–2024. - Miami Herald.

“Perversion of Justice: How Epstein Avoided Accountability.”

Investigative series, 2018–2019. - House Judiciary Committee.

“Request for Chain-of-Custody and Integrity Review of Epstein Evidence.”

Congressional correspondence, 2025.

- America First: Rhetoric vs. Reality

Most of us wanted AMERICANS first. Not Israel first, not Argentina first. Most of us wanted the truth about who the blackmail clients of Epstein were, and who was funding him. Most of us wanted MAGA, and Trump seems to have forgot that.

You can judge me for bEiNg A lEfTiSt RiNo. But I was never a republican. I was never totally right leaning, the extremists would SAY I am right wing, but I never have been full right. I am always center, and I am always going to point out BS if I see it.

Here is where the break happened for me.

HUD programs that directly help low income Americans were targeted for major reductions. Housing programs that keep people off the street, including project based vouchers and rental support programs, were put on the chopping block in the administration’s published 2025 proposals. The FY26 budget request sought a forty three percent cut to public housing, vouchers, and rental assistance, along with a twelve percent cut to homelessness programs. Section 8 was included in the list of programs that would see reduced funding.

Sources: https://www.nlihc.org/resource/trump-administration-releases-additional-details-fy26-budget-request-slashing-hud-rental, https://www.propublica.org/article/trump-budget-public-housing-funding-cuts

Then SNAP. During the SNAP freeze in 2025, states were told to pause or roll back benefits. This happened during the shutdown fight. The USDA told states to undo full SNAP payments for November and warned that any full benefit issuances were unauthorized. Millions of low income families were left with no benefits during the first half of November.

Sources: https://apnews.com/article/snap-benefits-trump-administration-demands-undo-states-d433f20df4d461db506e0d327a58d3c1, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/nov/10/snap-workers-trump-administration-funding

And the shutdown in 2025 made it even clearer. Democrats refused to agree to cuts to ACA premium tax credits and to new Medicaid restrictions. When the shutdown ended, the ACA subsidies that were expiring were not restored. Without these subsidies, insurers face higher unpaid medical costs and a risk pool that becomes more expensive. This cost increase does not stay inside the exchanges. Insurers raise premiums across the entire market, including employer and private plans.

Sources: https://www.medicarerights.org/medicare-watch/2025/11/13/shutdown-to-end-but-access-to-affordable-aca-marketplace-plans-still-at-risk, https://www.ajmc.com/view/government-shutdown-concluded-but-aca-subsidies-in-limbo, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/tracking-the-medicaid-provisions-in-the-2025-budget-bill

And here is another part that shows how broken this has become. During the campaign, Trump’s circle pushed the claim that he would release the Epstein files. Donald Trump Jr said transparency was coming. Kash Patel said full disclosure was coming. Others repeated that all visitor logs and records would be released if Trump won. In 2025, none of this happened. No files were released. The DOJ under Pam Bondi stated there was no client list and no credible evidence of blackmail.

Sources: https://www.newsweek.com/trump-epstein-files-maga-anger-fbi-patel-committee-2025-1923459, https://www.newsweek.com/pam-bondi-epstein-client-list-justice-department-statement-2025-1923375

And the idea that only Trump was connected to Epstein is false. Epstein’s network included figures from both political parties. Bill Clinton had multiple documented flights on Epstein’s jet. Major Democratic donors and academics had documented associations. Unsealed documents in 2024 listed more than one hundred seventy Epstein associates across politics, business, and academia.

Sources: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/jan/04/epstein-documents-unsealed-list, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/10/us/epstein-gates-ito-mit.html

So when political influencers promise transparency and deliver nothing, and when both sides point fingers while ignoring their own, it shows the depth of the problem. The system protects powerful circles, not Americans.

So when I hear America First, but I see cuts to housing support, food support, healthcare support, and silence on the Epstein disclosures that were promised, it does not match. The Americans losing Section 8, losing SNAP, losing affordable insurance, and losing Medicaid support are Americans. Kids. Parents. Seniors. Veterans. Working poor.

I am still all about making America great again. I always have been. I just do not think Trump is heading in that direction anymore, and many are locked into loyalty that prevents them from admitting what is in front of them.

If we say America First, then the people living on American soil, struggling, should not be last.

- Michigan’s Property Tax CrossroadsExplain funding shift. Goal -> Inform. Viz -> HTML/CSS diagram. Interaction -> None. Justification -> A simple, static visual is the clearest way to show the ‘before’ and ‘after’ of the money trail. Method -> Tailwind Flexbox. 2. Local Budget Simulation: Info -> Local service funding. Goal -> Compare. Viz -> Doughnut Chart. Interaction -> Buttons toggle data between ‘Local Control’ and ‘State Control’ scenarios. Justification -> Interactively showing how funding priorities could be forcibly changed is far more impactful than text alone. Library -> Chart.js. 3. Eaton County Township Funding Divide: Info -> Disparate voting outcomes. Goal -> Organize/Compare. Viz -> Simplified HTML/CSS map/blocks. Interaction -> Clicking on regions updates a text panel with specific outcomes. Justification -> This visually represents the urban/rural divide and connects geography to policy consequences. Method -> HTML/CSS/JS. (Title changed from ‘Millage Map’ to ‘Funding Divide’ for accuracy.) 4. Service Impact Cards: Info -> Cuts to local services. Goal -> Inform. Viz -> Icon-based cards. Interaction -> None. Justification -> A scannable, visually clear format to present the direct, negative consequences of funding shortfalls. Method -> Tailwind Grid. 5. Urban vs. Rural Population: Info -> State political power balance. Goal -> Compare. Viz -> Bar Chart. Interaction -> None. Justification -> A bar chart provides an immediate, powerful visual of the population disparity that underpins the ‘loss of control’ argument for rural areas. Library -> Chart.js. –> /* Base styles suitable for embedding, minimizing external dependencies */ body { font-family: ‘Inter’, sans-serif; background-color: #f8fafc; /* slate-50 */ } /* Style to ensure Chart.js canvas respects its container for responsiveness */ .chart-container { position: relative; width: 100%; max-width: 450px; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; height: 300px; max-height: 400px; } @media (min-width: 768px) { .chart-container { height: 350px; } } /* Interactive styling for the map/block areas */ .map-area { transition: transform 0.2s ease-in-out, box-shadow 0.2s ease-in-out; } .map-area:hover { transform: translateY(-4px); box-shadow: 0 10px 15px -3px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.1), 0 4px 6px -2px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.05); } .map-area.active { transform: translateY(-2px); box-shadow: 0 0 0 3px #fbbf24; /* amber-400 */ } /* Custom scroll-margin for sticky nav targets */ .scroll-mt-20 { scroll-margin-top: 5rem; }

Michigan’s Property Tax Repeal: Who Really Loses Control?

A citizen-led movement, **AxMITAX**, proposes eliminating all property taxes in Michigan. Proponents promise the largest tax cut in state history, but critics warn of a catastrophic loss of local control, shifting funding power to Lansing and threatening essential services. This analysis explores the proposal’s mechanics, the risks to community autonomy, and the real-world consequences already unfolding in places like **Eaton County**.

How Local Funding Would Change

The core of the debate centers on who controls the purse strings: local voters or state legislators. The AxMITAX plan would replace dedicated, locally controlled property tax revenue with state-allocated funds from increased sales and excise taxes.

Current System: Local Control

1Property owners pay taxes **directly** to local municipalities (city, township, county).

▼2Local elected officials set millage rates based on **community needs and voter approval**.

▼3Funds are used for specific local services: police, fire, libraries, parks, and roads.

Proposed AxMITAX System: State Control

1Property taxes are eliminated. The state increases the **sales tax** and adds new excise taxes.

▼2All tax revenue goes to a **state-controlled fund in Lansing**.

▼3The state legislature allocates funds back to communities, with **no guarantee** they match local needs or priorities.

Simulating the Impact on a Local Budget

Local property taxes give communities **direct control** over service funding. This simulation shows how a typical local budget might be re-prioritized if funding decisions were shifted to the state level, where local needs may be overlooked. Click the buttons to see the potential shift.

Policy analysts and the Michigan Municipal League (MML) have highlighted the dangers of shifting funding power to Lansing. The MML suggests this would be the most **’detrimental’ policy**, turning funding decisions into a political process that may not represent rural priorities or guarantee adequate school funding (WKAR, MML).

Eaton County on the Front Lines

Eaton County provides a stark, real-world example of what happens when communities face funding shortfalls. The current system relies on county-wide millage votes, but a growing divide between more prosperous townships and rural areas highlights the vulnerabilities.

Township Funding Divide: Delta vs. Rural Areas (Interactive)

Delta Township

Prosperous Area Vote Pattern

Rural Eaton County

Service-Dependent Area Vote Pattern

Click an area to see details

This illustrates how areas like **Delta Township** (Lansing State Journal) often pass dedicated local millages, ensuring their services are maintained, while rural communities remain vulnerable to failed **countywide** votes (Eaton County official millage info).

Consequences of Failed Millages: Services Cut

🚓Sheriff Patrols

After a failed millage, the Sheriff’s office faced a deficit and cut road patrols (Fox47News, WKAR). Local residents report a decline in public safety, noting, “We’re on our own out here,” reflecting the growing gap between service-rich and service-poor areas (Local Anecdote, WKAR).

🌳Parks & Recreation

County park maintenance has been reduced. In contrast, Delta Township maintains high-quality, programmed funding for its own parks, demonstrating the ability of wealthier areas to bypass the countywide service decline (Lansing State Journal, Local Anecdote).

🚌Public Transit

The Eaton County Transportation Authority (EATRAN) has faced funding deficits due to failed millage proposals (WKAR). This service reduction disproportionately affects rural, non-driving residents who rely on the service for essential needs.

Broader Implications: The Urban vs. Rural Power Dynamic

If AxMITAX passes, Eaton County’s internal conflicts would scale to a statewide level. Resource allocation would be influenced by the legislature, whose decisions are often guided by the priorities of dense, urban, and suburban population centers.

Michigan Population Distribution and Political Influence

This chart illustrates how the population of just a few major counties (e.g., Wayne, Oakland, Macomb) outweighs that of numerous rural counties combined. Rural, often ‘red’ counties risk losing autonomy entirely under a ‘blue’ majority state government that controls all resource allocation, a concern highlighted in public debates (Reddit/r/Michigan).

The elimination of property taxes promises relief, but the price is the fundamental power of local voters to fund their own police, parks, and schools. For less prosperous or rural communities, who stands to lose the most is clear: **those who can least afford to ‘do without’ will be subject to state-level political decisions made miles away.**

- Scriptures concerning the poor

Exodus 22:25 — If thou lend money to any of my people that is poor by thee, thou shalt not be to him as an usurer, neither shalt thou lay upon him usury. Do not exploit the poor when lending.

Exodus 23:6 — Thou shalt not wrest the judgment of thy poor in his cause. Do not deny justice to the poor in court.

Leviticus 19:9–10 — And when ye reap the harvest of your land, thou shalt not wholly reap the corners of thy field, neither shalt thou gather the gleanings of thy harvest. And thou shalt not glean thy vineyard, neither shalt thou gather every grape of thy vineyard; thou shalt leave them for the poor and stranger: I am the Lord your God. Leave food for the poor.

Leviticus 25:35 — And if thy brother be waxen poor, and fallen in decay with thee; then thou shalt relieve him: yea, though he be a stranger, or a sojourner; that he may live with thee. Relieve the poor so they may live.

Deuteronomy 15:7–8 — If there be among you a poor man of one of thy brethren within any of thy gates in thy land which the Lord thy God giveth thee, thou shalt not harden thine heart, nor shut thine hand from thy poor brother: But thou shalt open thine hand wide unto him, and shalt surely lend him sufficient for his need, in that which he wanteth. Do not harden your heart against the poor.

Deuteronomy 15:11 — For the poor shall never cease out of the land: therefore I command thee, saying, Thou shalt open thine hand wide unto thy brother, to thy poor, and to thy needy, in thy land. Command to always give generously.

Deuteronomy 24:12–15 — And if the man be poor, thou shalt not sleep with his pledge: In any case thou shalt deliver him the pledge again when the sun goeth down, that he may sleep in his own raiment, and bless thee: and it shall be righteousness unto thee before the Lord thy God. Thou shalt not oppress an hired servant that is poor and needy. Do not oppress poor workers.

Deuteronomy 26:12 — When thou hast made an end of tithing all the tithes of thine increase the third year, which is the year of tithing, and hast given it unto the Levite, the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow, that they may eat within thy gates, and be filled. Set aside tithes to feed the poor.

Job 5:15–16 — But he saveth the poor from the sword, from their mouth, and from the hand of the mighty. So the poor hath hope, and iniquity stoppeth her mouth. God delivers the poor.

Job 29:12 — Because I delivered the poor that cried, and the fatherless, and him that had none to help him. Job helped the poor and fatherless.

Job 30:25 — Did not I weep for him that was in trouble? was not my soul grieved for the poor? Job grieved for the poor.

Job 31:16–17 — If I have withheld the poor from their desire, or have caused the eyes of the widow to fail; Or have eaten my morsel myself alone, and the fatherless hath not eaten thereof. Job testifies he did not withhold from the poor.

Psalm 9:18 — For the needy shall not alway be forgotten: the expectation of the poor shall not perish for ever. The poor will not be forgotten by God.

Psalm 12:5 — For the oppression of the poor, for the sighing of the needy, now will I arise, saith the Lord; I will set him in safety from him that puffeth at him. God rises up because of oppression.

Psalm 34:6 — This poor man cried, and the Lord heard him, and saved him out of all his troubles. God hears and saves the poor.

Psalm 35:10 — All my bones shall say, Lord, who is like unto thee, which deliverest the poor from him that is too strong for him, yea, the poor and the needy from him that spoileth him? God delivers the poor from oppressors.

Psalm 37:14 — The wicked have drawn out the sword, and have bent their bow, to cast down the poor and needy, and to slay such as be of upright conversation. The wicked target the poor.

Psalm 40:17 — But I am poor and needy; yet the Lord thinketh upon me: thou art my help and my deliverer; make no tarrying, O my God. God is help to the poor.

Psalm 41:1 — Blessed is he that considereth the poor: the Lord will deliver him in time of trouble. Blessing for considering the poor.

Psalm 72:12–13 — For he shall deliver the needy when he crieth; the poor also, and him that hath no helper. He shall spare the poor and needy, and shall save the souls of the needy. God spares and saves the poor.

Psalm 82:3–4 — Defend the poor and fatherless: do justice to the afflicted and needy. Deliver the poor and needy: rid them out of the hand of the wicked. Command to defend the poor.

Proverbs 14:21 — He that despiseth his neighbour sinneth: but he that hath mercy on the poor, happy is he. Mercy on the poor brings blessing.

Proverbs 14:31 — He that oppresseth the poor reproacheth his Maker: but he that honoureth him hath mercy on the poor. Oppressing the poor insults God.

Proverbs 17:5 — Whoso mocketh the poor reproacheth his Maker: and he that is glad at calamities shall not be unpunished. Mocking the poor reproaches God.

Proverbs 19:17 — He that hath pity upon the poor lendeth unto the Lord; and that which he hath given will he pay him again. Helping the poor is lending to God.

Proverbs 21:13 — Whoso stoppeth his ears at the cry of the poor, he also shall cry himself, but shall not be heard. Ignoring the poor leads to being ignored.

Proverbs 22:9 — He that hath a bountiful eye shall be blessed; for he giveth of his bread to the poor. Blessing for generosity.

Proverbs 22:22–23 — Rob not the poor, because he is poor: neither oppress the afflicted in the gate: For the Lord will plead their cause, and spoil the soul of those that spoiled them. Do not rob or oppress the poor.

Proverbs 28:27 — He that giveth unto the poor shall not lack: but he that hideth his eyes shall have many a curse. Giving prevents lack, hiding brings curses.

Proverbs 29:7 — The righteous considereth the cause of the poor: but the wicked regardeth not to know it. The righteous care about the poor.

Proverbs 31:9 — Open thy mouth, judge righteously, and plead the cause of the poor and needy. Defend the poor and needy.

Isaiah 1:17 — Learn to do well; seek judgment, relieve the oppressed, judge the fatherless, plead for the widow. Command to relieve the oppressed.

Isaiah 3:15 — What mean ye that ye beat my people to pieces, and grind the faces of the poor? saith the Lord God of hosts. Condemnation for crushing the poor.

Isaiah 10:2 — To turn aside the needy from judgment, and to take away the right from the poor of my people, that widows may be their prey. Condemnation of injustice against the poor.

Isaiah 25:4 — For thou hast been a strength to the poor, a strength to the needy in his distress, a refuge from the storm, a shadow from the heat. God is strength for the poor.

Isaiah 41:17 — When the poor and needy seek water, and there is none, I the Lord will hear them. God promises to hear the poor.

Isaiah 58:7 — Is it not to deal thy bread to the hungry, and that thou bring the poor that are cast out to thy house? when thou seest the naked, that thou cover him? True religion is feeding the poor.

Jeremiah 22:16 — He judged the cause of the poor and needy; then it was well with him: was not this to know me? saith the Lord. Knowing God means defending the poor.

Ezekiel 16:49 — Behold, this was the iniquity of thy sister Sodom, pride, fulness of bread, and abundance of idleness, neither did she strengthen the hand of the poor and needy. Sodom’s sin included neglecting the poor.

Ezekiel 18:7 — And hath given his bread to the hungry, and hath covered the naked with a garment. The righteous feed and clothe the poor.

Ezekiel 22:29 — The people of the land have used oppression, and exercised robbery, and have vexed the poor and needy. Condemnation of oppressing the poor.

Amos 2:6 — They sold the righteous for silver, and the poor for a pair of shoes. Condemnation for selling the poor.

Amos 5:11 — Forasmuch therefore as your treading is upon the poor, and ye take from him burdens of wheat. Woe to those who trample the poor.

Amos 8:6 — That we may buy the poor for silver, and the needy for a pair of shoes. Condemnation for exploiting the poor.

Zechariah 7:10 — And oppress not the widow, nor the fatherless, the stranger, nor the poor. Do not oppress the poor.

Malachi 3:5 — And I will come near to you to judgment; and I will be a swift witness against those that oppress the hireling in his wages, the widow, and the fatherless. God will judge oppressors of the poor.

Matthew 6:3–4 — But when thou doest alms, let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth: That thine alms may be in secret. Give to the poor in secret.

Matthew 19:21 — If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven. Jesus commands giving to the poor.

Matthew 25:35 — For I was an hungred, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in. The righteous are praised for helping the needy.

Mark 10:21 — One thing thou lackest: go thy way, sell whatsoever thou hast, and give to the poor. Giving to the poor is following Christ.

Mark 12:43 — This poor widow hath cast more in, than all they which have cast into the treasury. God values the poor widow’s gift.

Luke 3:11 — He that hath two coats, let him impart to him that hath none; and he that hath meat, let him do likewise. Share food and clothing.

Luke 4:18 — The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor. Jesus’ mission includes the poor.

Luke 6:20 — Blessed be ye poor: for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessing to the poor.

Luke 6:30 — Give to every man that asketh of thee; and of him that taketh away thy goods ask them not again. Give freely.

Luke 12:33 — Sell that ye have, and give alms; provide yourselves bags which wax not old. Give to the poor and gain treasure in heaven.

Luke 14:13 — But when thou makest a feast, call the poor, the maimed, the lame, the blind. Invite the poor and needy.

Luke 16:20–21 — And there was a certain beggar named Lazarus, which was laid at his gate, full of sores. The rich man is condemned for neglecting Lazarus.

Luke 19:8 — Behold, Lord, the half of my goods I give to the poor. Zacchaeus pledges to give to the poor.

Acts 2:44–45 — And all that believed were together, and had all things common; And sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need. Early church shared with the poor.

Acts 4:34–35 — Neither was there any among them that lacked: for as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them, and brought the prices of the things that were sold. No believer lacked because they gave to the poor.

Acts 11:29 — Then the disciples, every man according to his ability, determined to send relief unto the brethren which dwelt in Judaea. Disciples sent aid to the poor.

Acts 20:35 — It is more blessed to give than to receive. Command to support the weak.

Romans 12:13 — Distributing to the necessity of saints; given to hospitality. Share with those in need.

Romans 15:26 — To make a certain contribution for the poor saints which are at Jerusalem. Churches gave to the poor.

2 Corinthians 8:14 — But by an equality, that now at this time your abundance may be a supply for their want. Give from abundance to supply needs.

2 Corinthians 9:7 — Every man according as he purposeth in his heart, so let him give; not grudgingly. God loves cheerful giving.

Galatians 2:10 — Only they would that we should remember the poor; the same which I also was forward to do. Apostles commanded remembrance of the poor.

Ephesians 4:28 — Let him that stole steal no more: but rather let him labour, that he may have to give to him that needeth. Work to give to the poor.

1 Timothy 6:18 — That they do good, that they be rich in good works, ready to distribute, willing to communicate. The rich are commanded to give.

Hebrews 13:16 — But to do good and to communicate forget not: for with such sacrifices God is well pleased. Do not forget to share.

James 1:27 — Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this, To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction. True religion is helping the poor.

James 2:5–6 — Hath not God chosen the poor of this world rich in faith? But ye have despised the poor. Condemnation for scorning the poor.

James 2:15–16 — If a brother or sister be naked, and destitute of daily food, And one of you say unto them, Depart in peace, be ye warmed and filled; notwithstanding ye give them not those things which are needful. Faith without helping the poor is worthless.

1 John 3:17 — But whoso hath this world’s good, and seeth his brother have need, and shutteth up his bowels of compassion from him, how dwelleth the love of God in him? Withholding from the poor proves no love of God.